Crankcase ventilation systems on Ventoux engines

Breathe or bust: how Renault solved crankcase ventilation on Ventoux engines of the 1950s and 1960s

The general principle

In a combustion engine, a small part of the gases in the combustion chamber pass between the piston rings into the crankcase: this is known as blow-by.

This mixture of gases and oil vapor increases the internal pressure and, if not properly evacuated, ends up pushing the oil through any weak point: seals, oil seals or even the dipstick.

The mission of the crankcase ventilation system is as simple as it is vital: to keep the internal pressure balanced and allow these gases to escape without entraining oil.

In modern engines, a PCV valve connects the crankcase to the intake, using the manifold vacuum to draw in gases.

The main function of the crankcase breather is to relieve the pressure built up by the blow-by gases leaking from the cylinders, preventing this pressure from forcing the oil out through seals and gaskets. If the ventilation is deficient or obstructed, the engine will try to expel the pressure “wherever it can”, causing oil leaks at oil seals, gaskets and even causing the dipstick to partially pop out. This system is often overlooked, but in veteran engines inadequate ventilation can be the “silent culprit” of abnormal oil consumption and persistent leaks.

Crankcase breathing in Ventoux engines

Renault Ventoux engines (4CV, Dauphine, Gordini, Ondine and early Floride) had no intake depression: they relied on passive vents and the balance of natural pressures inside the block and employed an open system that let gases and oil vapors escape directly to the atmosphere.

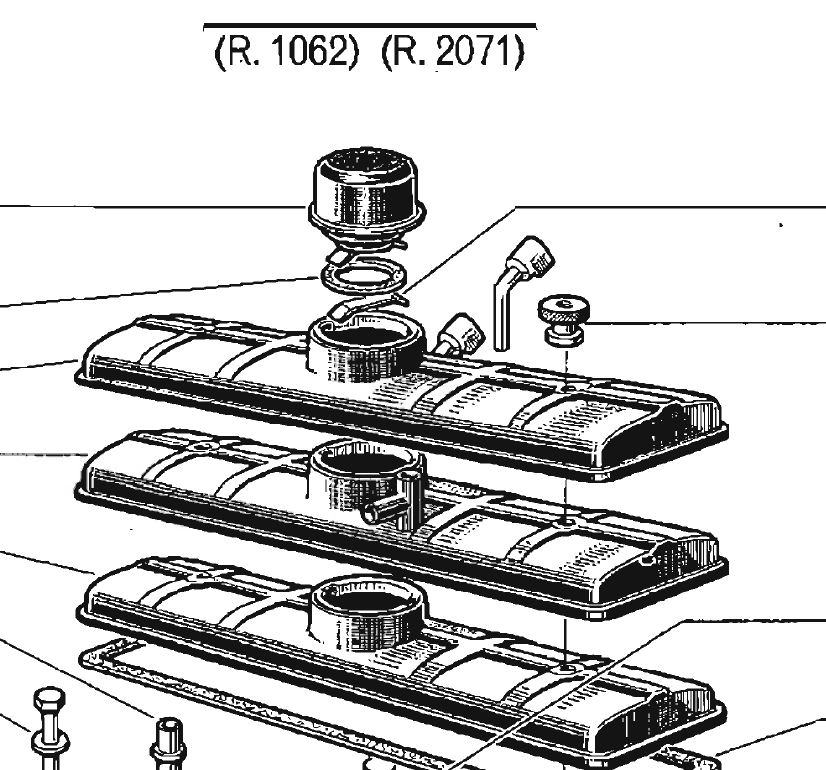

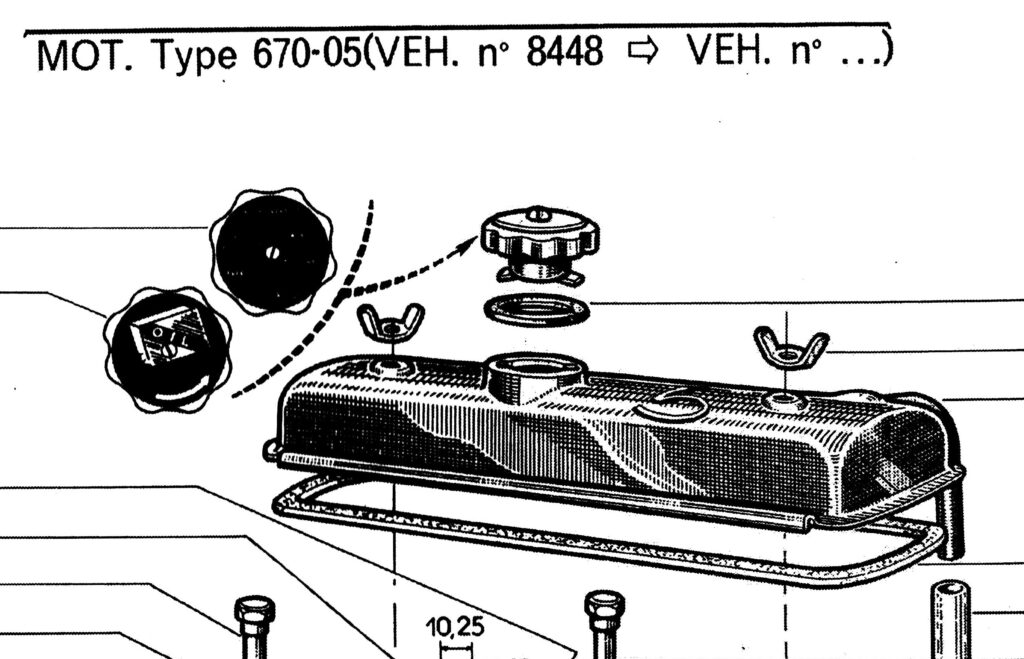

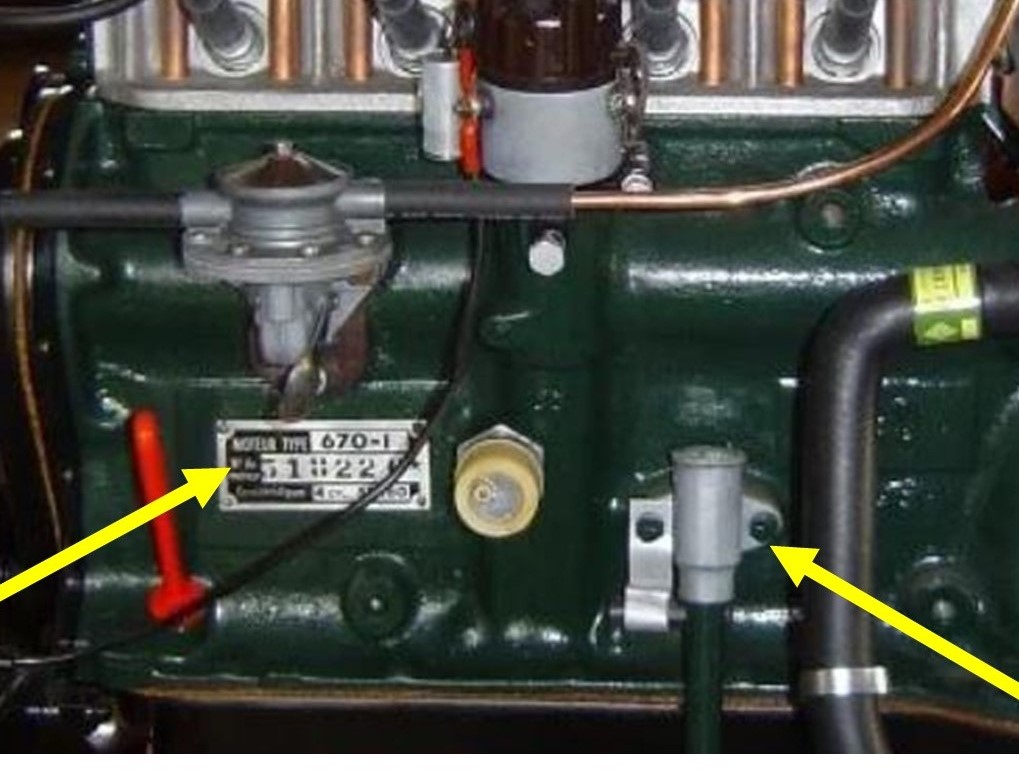

Throughout the life of the Ventoux engine, Renault adopted different solutions: from simple breather caps with grille, to vent pipes located in the rocker cover or in the block. Below, we will see the historical evolution of these solutions according to the versions of the engine (identified by references such as Type 662 on the 4CV, 670-01/02 on standard Dauphine, 670-04 and 670-05 on Dauphine Gordini.

First versions: Renault 4CV (Type 662 engine)

The small Renault 4CV, produced since 1947, inaugurated the Billancourt/Ventoux engine family with displacements of 760 cc (initial version Type 662-1) and then 747 cc (Type 662-2). In its early years, the crankcase ventilation of the 4CV was entrusted to :

- A breather was the oil filler cap itself, designed with an internal filter element to let the vapors escape. This configuration was typical for engines of the time, with no air cleaner connections or check valves.

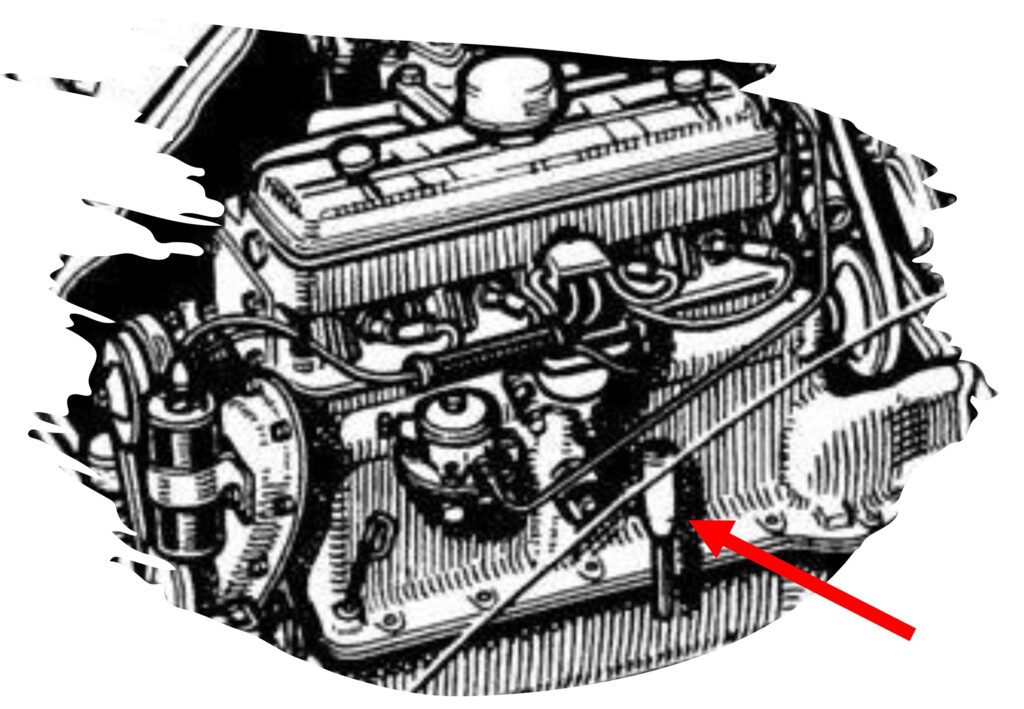

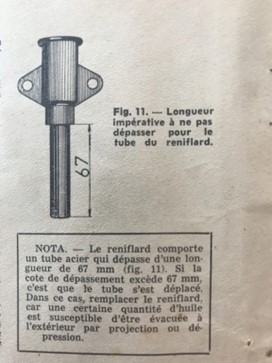

- A vent on the right side of the engine block that evacuated the excess pressure to the atmosphere. A vent whose tube length (exactly 67 mm) was carefully measured to generate the outflow of gases, surely helping their evacuation by Venturi effect during the running of the vehicle, and avoiding that this vent became a source of “back pressure” towards the crankcase (causing the opposite effect to the desired one). You can see here an illustration of the manual of the time

On some later versions of the Renault 4CV it is possible to find an additional breather pipe located at the top of the engine. This pipe came out of the rocker cover and allowed a more efficient “venting” of the crankcase gases.

In other words, the 4CV (depending on the versions) came to have three breathing points available in which it was possible to install closed plug having then either two breathing points (pipette in the engine block+outlet pipe of the rocker cover)- or three ventilation points (pipette in the engine block+outlet pipe of the rocker cover+ventilated plug).

Be that as it may, the criticality of these points is empirically proven and there have been 4CV owners who have reported that a cleaning of these vents has immediate effects: “I cleaned the bouchon reniflard and it seems that the engine no longer leaks oil” said an owner of a 1959 4CV which illustrates how the clogging of the vented plug could cause leaks that were solved by restoring the ventilation (actually we can also attest to this :-)).

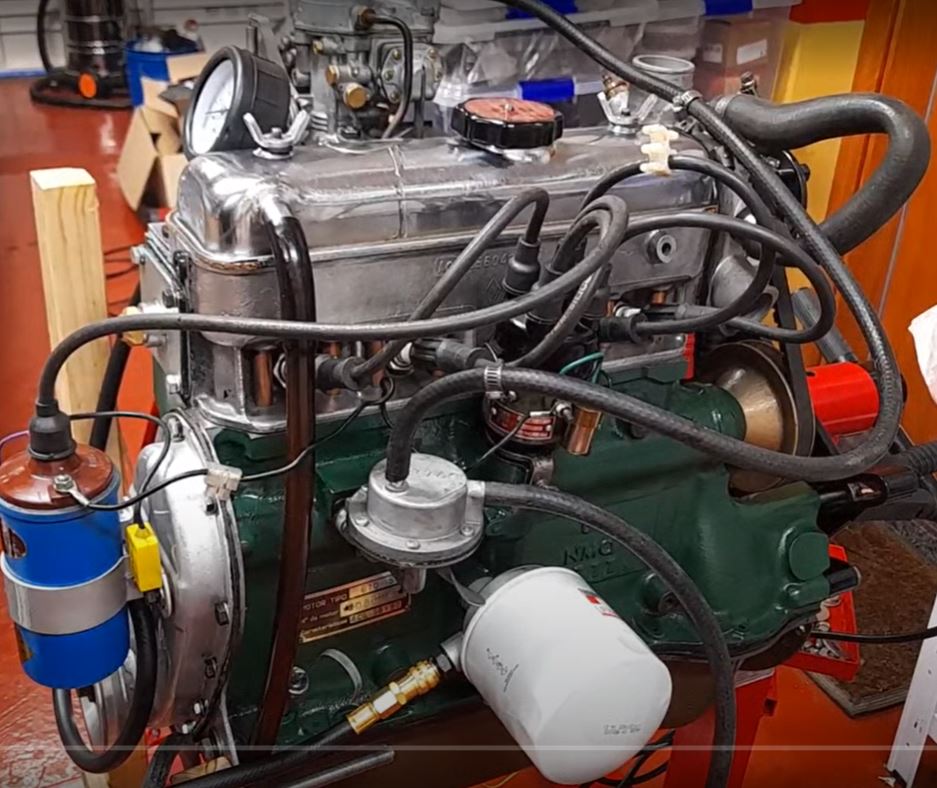

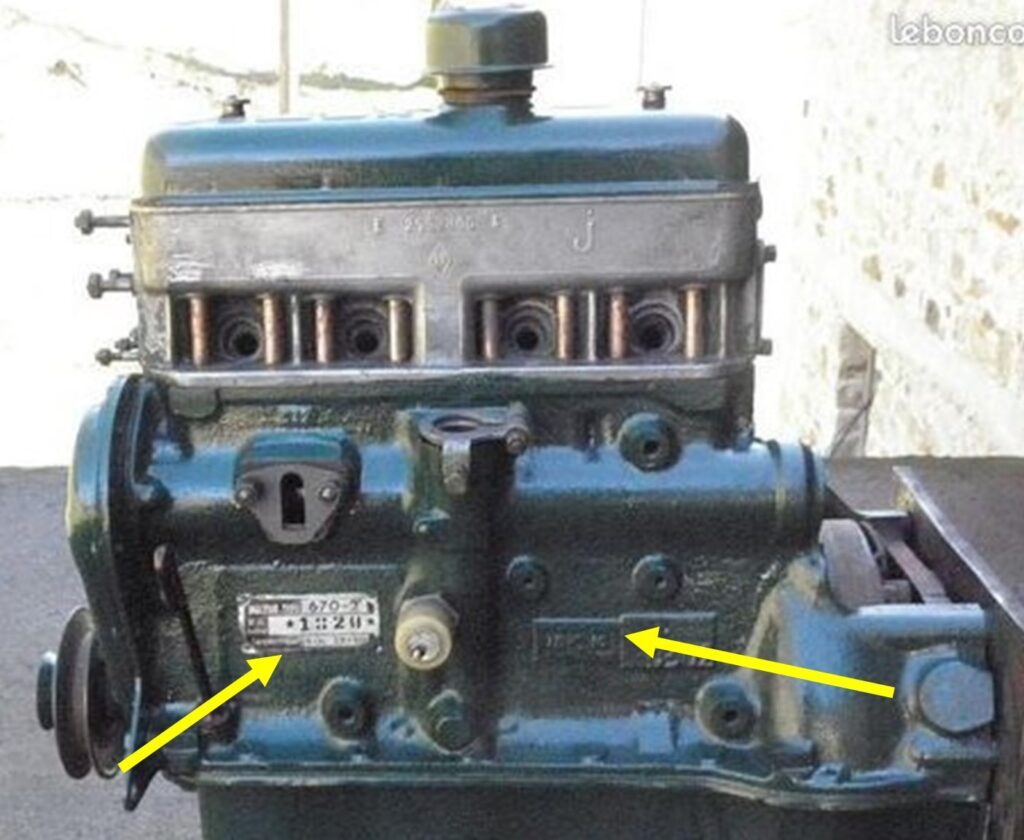

First image (photo), the classic Renault 4CV engine block side reniflard: a calibrated tube that evacuates crankcase vapors to the outside.

Second image (drawing), the original diagram from the workshop manual indicating the exact length (67 mm) that the tube must protrude, essential to avoid both air suction by Venturi effect and the projection of oil to the outside.

Renault Dauphine standard (engine Type 670)

The Renault Dauphine (project R1090), launched in 1956, equipped an enlarged version of the Ventoux engine – 845 cc – known as Type 670-01 (27-31 hp according to standard). From its inception, the Dauphine incorporated a venting system very similar to the later 4CV scheme, i.e. with a fixed breather mounted on the block plus a vented filler cap. The block-mounted breather system disappeared on the 670-02 engine and no longer appeared on the Dauphine (or Gordini), leaving either the vented plug, the side pipe (670-05) or a combination of the two.

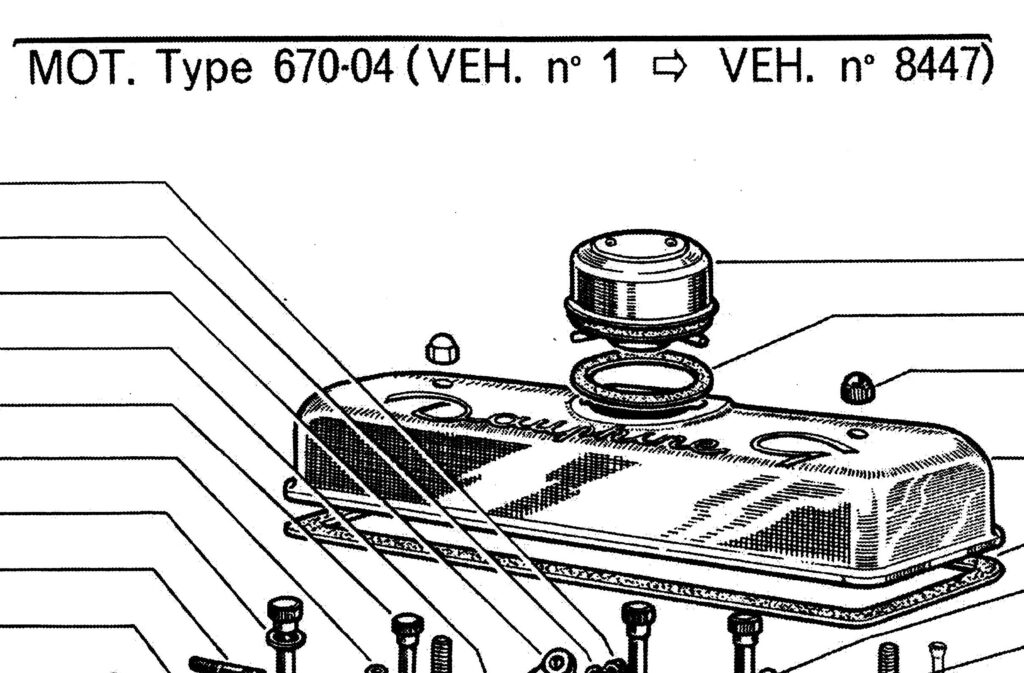

On the Renault 670-04 engine, crankcase ventilation was provided by a filler cap with integrated breather, visible on the top of the rocker cover. This plug, equipped with a small metal filtering screen, allowed the crankcase gases to pass to the outside, keeping the internal pressure balanced.

The cover also incorporated a small inner baffle that acted as an oil separator, preventing the droplets in suspension from escaping together with the vapors. This system, although simple, proved effective for the speeds and operating conditions of the standard Dauphine and was the basis on which Renault evolved the later 670-05 type Ventoux engines of the Gordini versions.

Be that as it may, the function of both the vented plug and the rocker cover gas outlet was to retain the oil particles (which drained back into the engine) and let only the gases pass through.

The Dauphine, like the R4CV, did not recirculate these gases to the intake either; it simply expelled them. As a technical publication points out, the Ventoux engines relied on these direct atmospheric exhausts for all their ventilation.

In practice, a Dauphine in good condition hardly smoked at all from the breather; but on worn units it was notorious to see the “second exhaust” blowing bluish-white smoke from the rocker cover tube. This was a symptom of excessive

Gordini sport versions: engines 670-05

Renault offered from 1957-58 a powered version of the Dauphine developed by Amédée Gordini. At the end of 1960, an evolution identified as Type 670-05 appeared, power 40 hp SAE, ~36 hp DI but with internal design changes. As for the crankcase ventilation system, were there any differences?

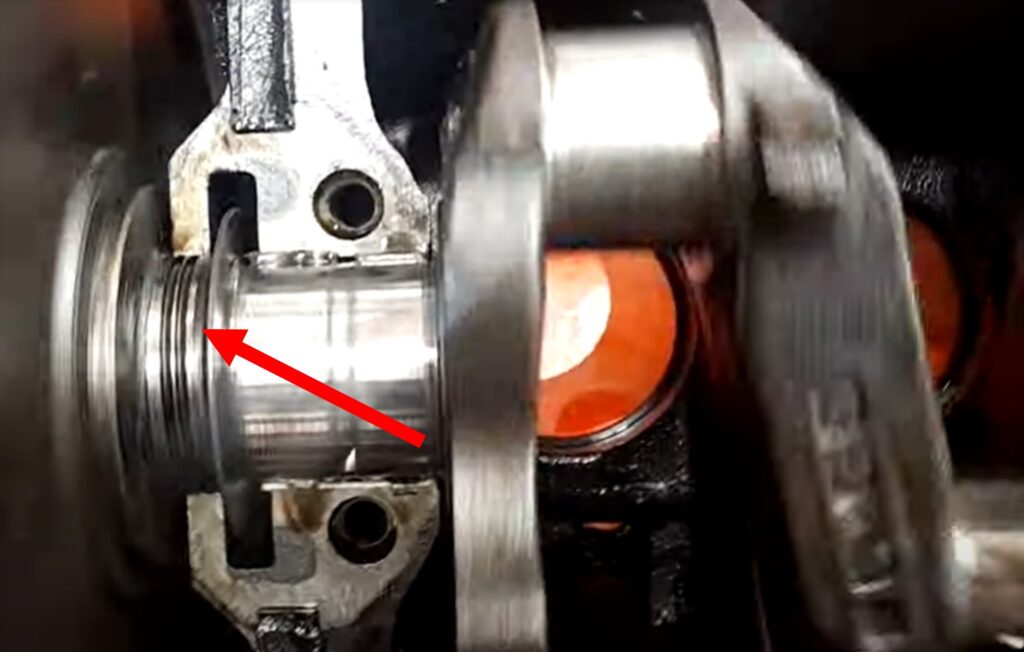

The answer is yes, mainly related to improvements in the oil retention system on the rear crankshaft (i.e. gearbox side).

On the 670-05 engine (used since 1960 on Gordini R1091/1092, and also on the base R8 years later) a modification was introduced at the rear of the crankshaft: a helical “pigtail” spline around the rear journal, the effect of which was to return the oil to the engine by centrifugal action.

This design (similar to that used in VW and other engines of the time) improved the sealing at the rear outlet , reducing oil leakage, although it still did not include a rubber oil seal. Renault, relying on this improvement, eliminated the vented oil plug on the 670-05, equipping them with a normal sealed plug. In other words, on the 670-05 Gordini the only active breathing passage was the upper crankcase tube (cache-culbuteurs).

In theory, the “pigtail” propeller should have been sufficient to control the oil and the original ventilation was sufficient. What could happen in practice?

- For the breather, the oil/gas filtration area is on the inside of the rocker cover so a dirt blockage is not obvious to see. And if that outlet is clogged, the fact that it is the only one means that the crankcase gas evacuation functionality is seriously compromised.

- If for some reason an older crankshaft is fitted to a 670-05 engine – only with straight splines which, although less effective than the “queue de couchon” or “pigtail” spiral for retaining oil is technically possible – the original venting may be insufficient.

Just this happened in the restoration of our Gordini a few weeks ago: a new crankshaft from old stock (fine spline type, corresponding to 670-04 engine) was installed in a 670-05 block. The result was that, even with a clean cover breather, the engine was still leaking some oil out of the clutch bell under demanding use.

It is important to mention that oil retention systems without rubber seals based on spline or coil machining work well, but they are based on one premise: The pressures on both sides of the oil sump wall must be balanced. An overpressure will cause the grooves or spirals to become precisely the outlet path.

And one solution is to add the ventilation that these “old” single spline crankshafts lacked: replace the hermetic plug with a vented oil filler cap, of the same type used on earlier Ventoux engines (some 4CV, Juvaquatre and standard Dauphine). This special cap incorporates a vent with a screen, increasing the crankcase ventilation flow.

With the additional vented plug, the problem of overpressure – and oil ‘release’ – on our Gordini disappeared completely. In fact, Renault itself re-employed both vents on the Dauphine 1093 racing version (1962-63, ~55 hp), thus ensuring maximum vapor evacuation in extreme use. Manuals of the time stressed the importance of keeping the breather screen clean and the duct clear.

How to check the ventilation system on a Ventoux engine

At the time it was attributed to a possible crack in the crankcase, deteriorated seals or even to an additive that had been added days before to “clean” the lubrication circuit.

- Check the rocker cover:

- Disassemble and thoroughly clean the inner chamber. You can do this with gasoline and a brush or with a powerful engine degreaser.

- Make sure that the 14 mm outlet is not obstructed by old deposits.

- If the pipe has a bend or extension, check that there is no condensate or solidified oil inside.

- Check the side tube of the block (if any):

- Check length and position (on 4CV: 67 mm from its base).

- Confirm that the pipe is not bent or clogged with paint, putty or dirt.

- Check for oil residues: a light film is normal, continuous dripping is not.

- Oil plug:

- If it is of the ventilated type, clean the internal metal mesh with gasoline or solvent.

- If it is closed and there is no other active vent that you suspect, you can temporarily replace it with a vented one to see if the leaks disappear. You can get it here (Spain) y here (France)

- Practical test: with the engine idling, put your hand around the breather outlets. You should notice a soft, pulsating “knocking” sound at the engine’s rhythm of the gases coming out. If you accelerate gently, you should not notice any smoke.

Technical conclusion

In all engines, crankcase ventilation is not a minor detail: it is part of the dynamic balance of the engine.

If you notice significant oil leaks or drops in oil level that you are unable to explain, consider whether the crankcase breather may be the cause. Keep in mind that if there is overpressure, the vapors will try to escape through the easiest or weakest point. In our case they escaped first by breaking a deteriorated oil seal, and then through the rear crankshaft outlet.

In the case of overpressure losses, it is easy to confuse the consequences with the causes.

For Ventoux engines : A clean vented plug, a clear rocker cover tube and – if present – a properly calibrated side breather ensure the right pressure in the crankcase and prevent leaks without the need for additives or miracles. For any engine in your car, I suggest you look in the technical documentation because you will surely find where to do the oil sump breather checks.